While gradient descent can be used to (attempt to) minimize any differentiable function , we typically use it to minimize empirical risk functions, .

Let’s try using gradient descent to fit a linear regression model – that is, let’s use it to minimize

This function has a closed-form solution, but it’s worthwhile to see how gradient descent works on it.

In Chapter 8.1, we found that the gradient of is

so, the update rule is

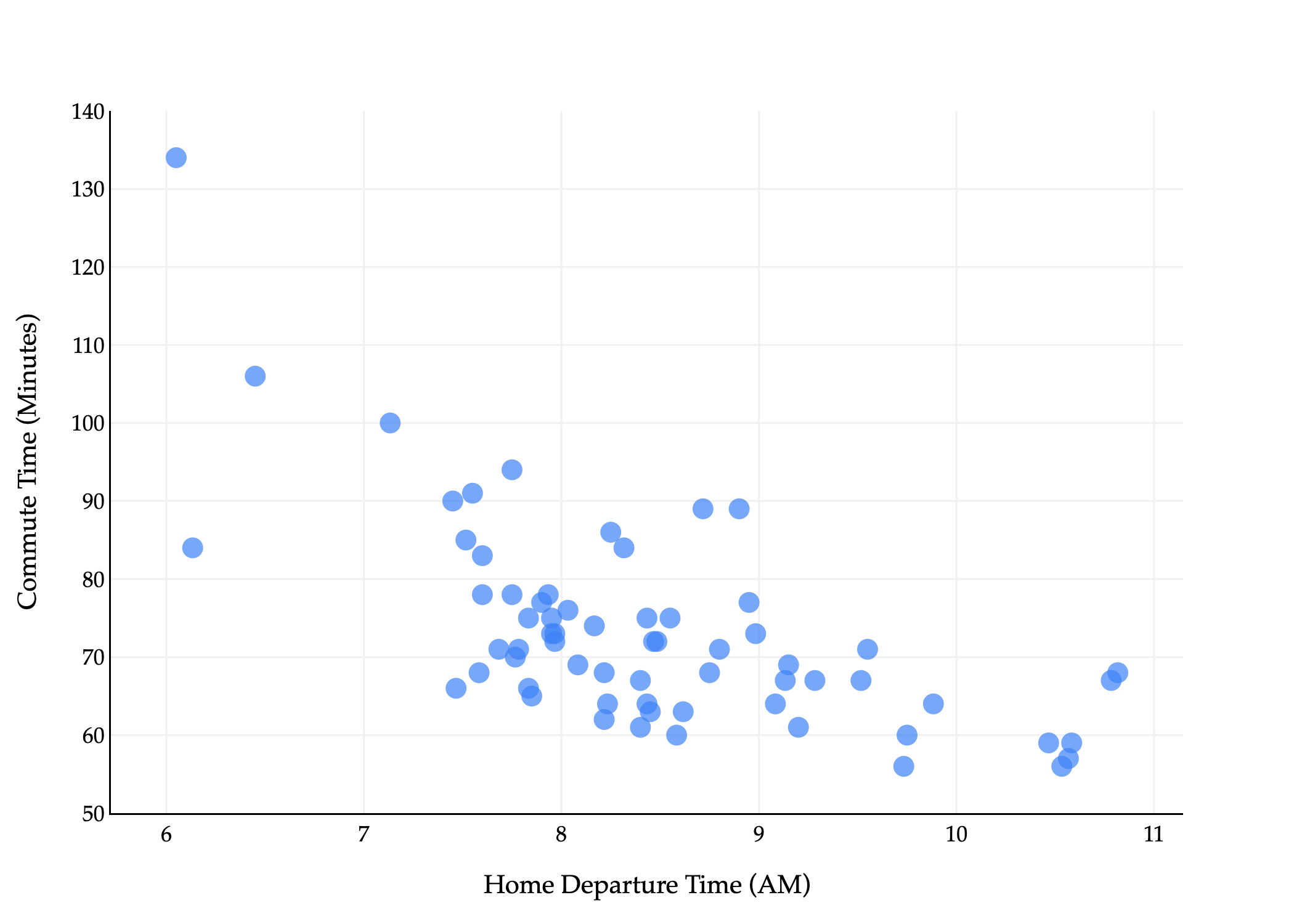

Let’s start by using gradient descent to fit a simple linear regression model to predict commute times in minutes from departure_hour – a problem we’ve solved many times.

We now apply gradient descent to empirical risk minimization.

More to come! We’ll cover this example on Tuesday, and talk more about convexity (and, time permitting, variants of gradient descent for large datasets).