Symmetric matrices – that is, square matrices where – behave really nicely through the lens of eigenvectors, and understanding exactly how they work is key to Chapter 10.1, when we generalize beyond square matrices.

If you search for the spectral theorem online, you’ll often just see Statement 4 above; I’ve broken the theorem into smaller substatements to see how they are chained together.

The proof of Statement 1 is beyond our scope, since it involves fluency with complex numbers. If the term “complex conjugate” means something to you, read the proof here – it’s relatively short.

Statement 2 was proved in Lab 11, Activity 5.

I’m not going to cover the proof of Statement 3 here, as I don’t think it’ll add to your learning.

Orthogonal matrices satisfy , meaning their columns (and rows) are orthonormal, not just orthogonal to one another. The fact that means that , so taking the transpose of a matrix is the same as taking its inverse.

So, instead of

we’ve “upgraded” to

This is the main takeaway of the spectral theorem: that symmetric matrices can be diagonalized by an orthogonal matrix. Sometimes, is called the spectral decomposition of , but all it is is a special case of the eigenvalue decomposition for symmetric matrices.

Visualizing the Spectral Theorem¶

Why do we prefer over ? Taking the transpose of a matrix is much easier than inverting it, so actually working with is easier.

But it’s also an improvement in terms of interpretation: remember that orthogonal matrices are matrices that represent rotations. So, if is symmetric, then the linear transformation is a sequence of rotations and stretches.

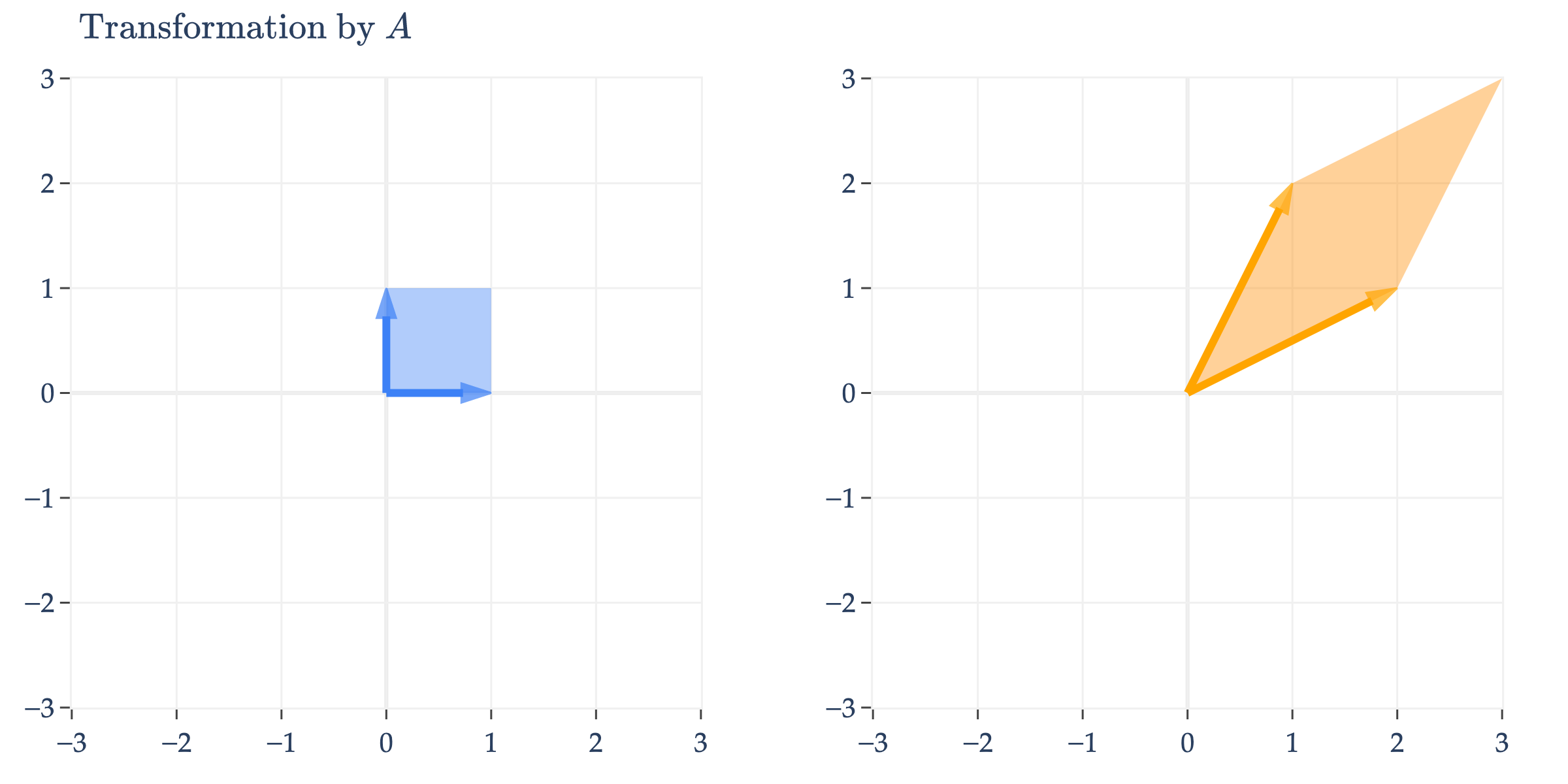

Let’s make sense of this visually. Consider the symmetric matrix .

We now focus on symmetric matrices and the spectral theorem.

appears to perform an arbitrary transformation; it turns the unit square into a parallelogram, as we first saw in Chapter 6.1.

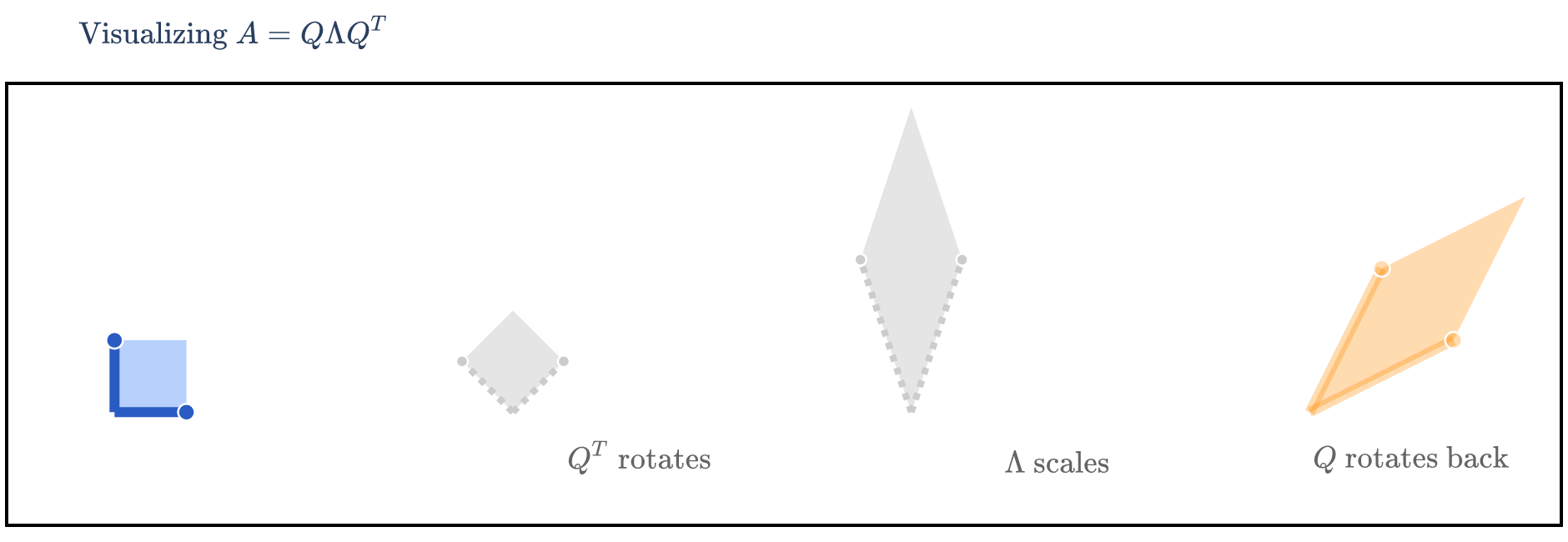

But, since is symmetric, it can be diagonalized by an orthogonal matrix, .

has eigenvalues with eigenvector and with eigenvector . But, the ’s I’ve written aren’t unit vectors, which they need to be in order for to be orthogonal. So, we normalize them to get and . Placing these ’s as columns of , we get

and so

We’re visualizing how turns into , i.e. how turns into . This means that we first need to consider the effect of on , then the effect of on that result, and finally the effect of on that result – that is, read the matrices from right to left.

The Ellipse Perspective¶

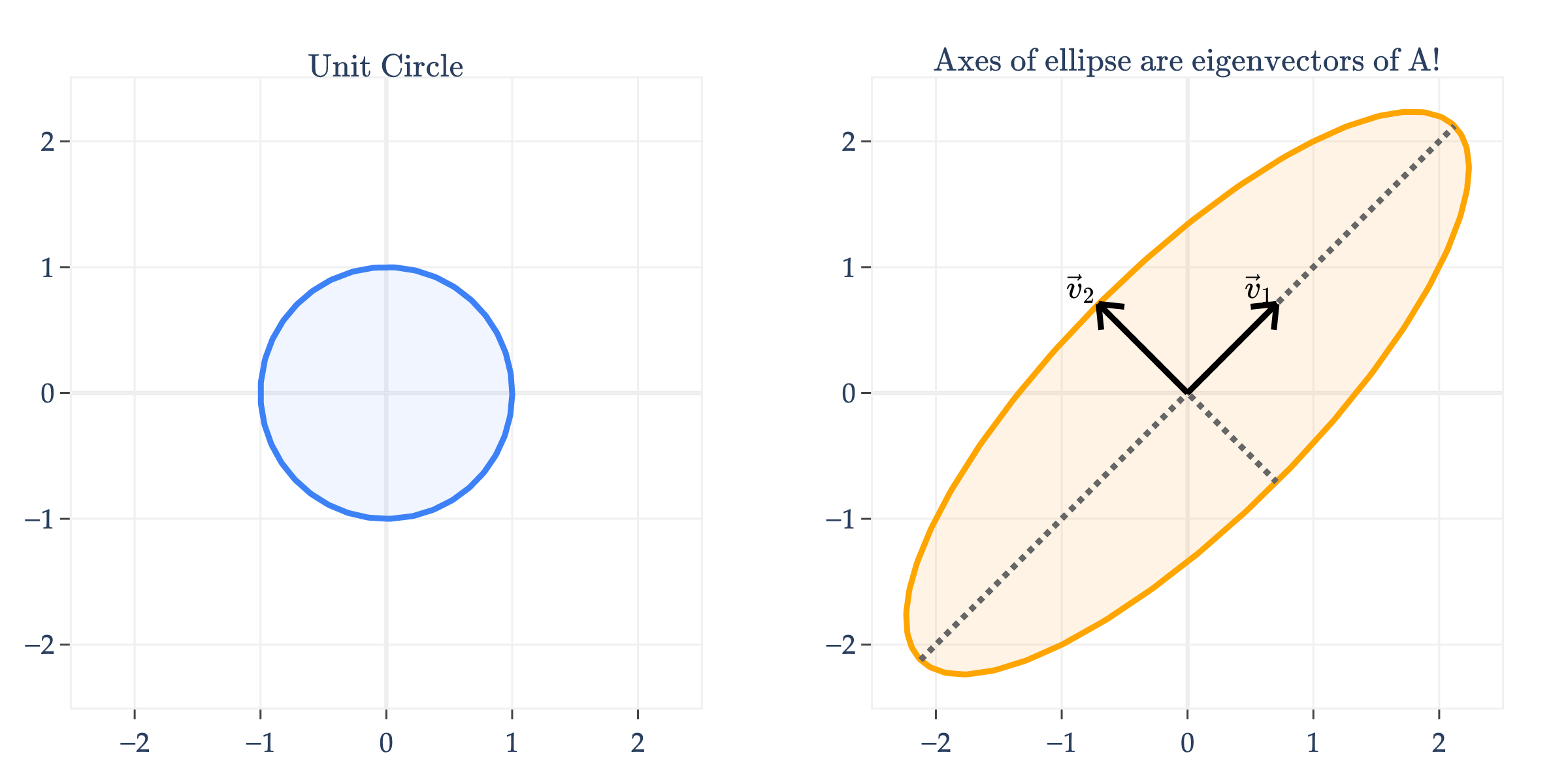

Another way of visualizing the linear transformation of a symmetric matrix is to consider its effect on the unit circle, not the unit square. Below, I’ll apply to the unit circle.

Notice that transformed the unit circle into an ellipse. What’s more, the axes of the ellipse are the eigenvector directions of !

Why is one axis longer than the other? As you might have guessed, the longer axis – the one in the direction of the eigenvector – corresponds to the larger eigenvalue. Remember that has and , so the “up and to the right” axis is three times longer than the “down and to the right” axis, defined by .

To see why this happens, consult the solutions to Lab 11, Activity 6b to try and derive it. It has to do with the expression ’s in that derivation. What are the ’s and where did the ’s come from?

Positive Semidefinite Matrices¶

I will keep this section brief; this is mostly meant to be a reference for a specific definition that you used in Lab 11 and will use in Homework 10.

What does this have anything to do with the diagonalization of a matrix? We just spent a significant amount of time talking about the special properties of symmetric matrices, and positive semidefinite matrices are a subset of symmetric matrices, so the properties implied by the spectral theorem also apply to positive semidefinite matrices.

Positive semidefinite matrices appear in the context of minimizing quadratic forms, . You’ve toyed around with this in Lab 11, but also note that in Chapter 8.1 we saw the most important quadratic form of all: the mean-squared error!

If we know all of the eigenvalues of in are non-negative, then we know that for all , meaning that the quadratic form has a global minimum. This is why, as discussed in Lab 11, the quadratic form is convex if and only if is positive semidefinite.

The fact that having non-negative eigenvalues implies the first definition of positive semidefiniteness is not immediately obvious, but is exactly what we proved in Lab 11, Activity 6.

A positive definite matrix is one in which for all , i.e. where all eigenvalues are positive, not just non-negative (0 is no longer an option).

Key Takeaways¶

The eigenvalue decomposition of a matrix is a decomposition of the form

where is a matrix containing the eigenvectors of as columns, and is a diagonal matrix of eigenvalues in the same order. Only diagonalizable matrices can be decomposed in this way.

The algebraic multiplicity of an eigenvalue is the number of times appears as a root of the characteristic polynomial of .

The geometric multiplicity of is the dimension of the eigenspace of , i.e. .

The matrix is diagonalizable if and only if any of these equivalent conditions are true:

has linearly independent eigenvectors.

For every eigenvalue , .

has distinct eigenvalues.

When is diagonalizable, it has an eigenvalue decomposition, .

If is a symmetric matrix, then the spectral theorem tells us that can be diagonalized by an orthogonal matrix such that

and that all of ’s eigenvalues are guaranteed to be real.

What’s next? There’s the question of how any of this relates to real data. Real data comes in rectangular matrices, not square matrices. And even it were square, how does any of this enlighten us?