Overview¶

The big concept introduced in Chapter 5.3 was the rank of a matrix, , which is the number of linearly independent columns of a matrix. The rank of a matrix told us the dimension of its column space, , which is the set of all vectors that can be created with linear combinations of ’s columns.

The ideas of rank, column space, and linear independence are all closely related, and also all apply for matrices of any shape – wide, tall, or square. This is good, because data from the real world is rarely square: we usually have many more observations () than features ().

The big idea in Chapters 6.1 and 6.2 is that of the inverse of a matrix, , which only applies to square matrices. But, inverses and square matrices can still be useful for our rectangular matrices with real data, since the matrix is square, no matter the shape of . And, as we discussed in Chapter 5.3 and you’re seeing in Homework 6, the matrix has close ties to the correlations between the columns of , which you already know has some connection to linear regression.

Linear Transformations¶

But first, I want us to think about matrix-vector multiplication as something more than just number crunching.

In Chapter 5.3, the running example was the matrix

To multiply by a vector on the right, that vector must be in , and the result will be a vector in .

Put another way, if we consider the function , maps elements of to elements of , i.e.

I’ve chosen the letter to denote that is a linear transformation.

Every linear transformation is of the form . For our purposes, linear transformations and matrix-vector multiplication are the same thing, though in general linear transformations are a more abstract concept (just like how vector spaces can be made up of functions, for example).

For example, the function

is a linear transformation from to , and is equivalent to

The function is also a linear transformation, from to .

A non-example of a linear transformation is

because no matrix multiplied by will produce .

Another non-example, perhaps surprisingly, is

This is the equation of a line in , which is linear in some sense, but it’s not a linear transformation, since it doesn’t satisfy the two properties of linearity. For to be a linear transformation, we’d need

for any . But, if we consider and as an example, we get

which are not equal. is an example of an affine transformation, which in general is any function that can be written as , where is an matrix and .

Activity 1¶

Activity 1

Activity 1.1

True or false: if is a linear transformation, then .

Activity 1.2

For each of the following functions, determine whether it is a linear transformation. If it is, write it in the form . If it is not, explain why not.

takes , multiplies the first component by 2 and second component by 3, and returns the difference between the two, as a scalar.

Solutions

Activity 1.1

True or false: if is a linear transformation, then .

True. Since is a linear transformation, we have

for any and . Plugging in , we get

Activity 1.2

is a linear transformation.

is a linear transformation.

is not a linear transformation. Notice the constant term of -5 in the first component! This is instead an affine transformation.

is not a linear transformation once again; it’s an affine transformation. If you don’t believe that it’s not a linear transformation, plug in both and ; if were a linear transformation, the latter output would be exactly double the former output.

This description tells us that , and this is a perfectly valid linear transformation, from to .

Linear Transformations from to ¶

While linear transformations exist from to or to , it’s in some ways easiest to think about linear transformations with the same domain and codomain, i.e. transformations of the form . This will allow us to explore how transformations stretch, rotate, and reflect vectors in the same space. Linear transformations with the same domain () and codomain () are represented by matrices, which gives us a useful setting to think about the invertibility of square matrices, beyond just looking at a bunch of numbers.

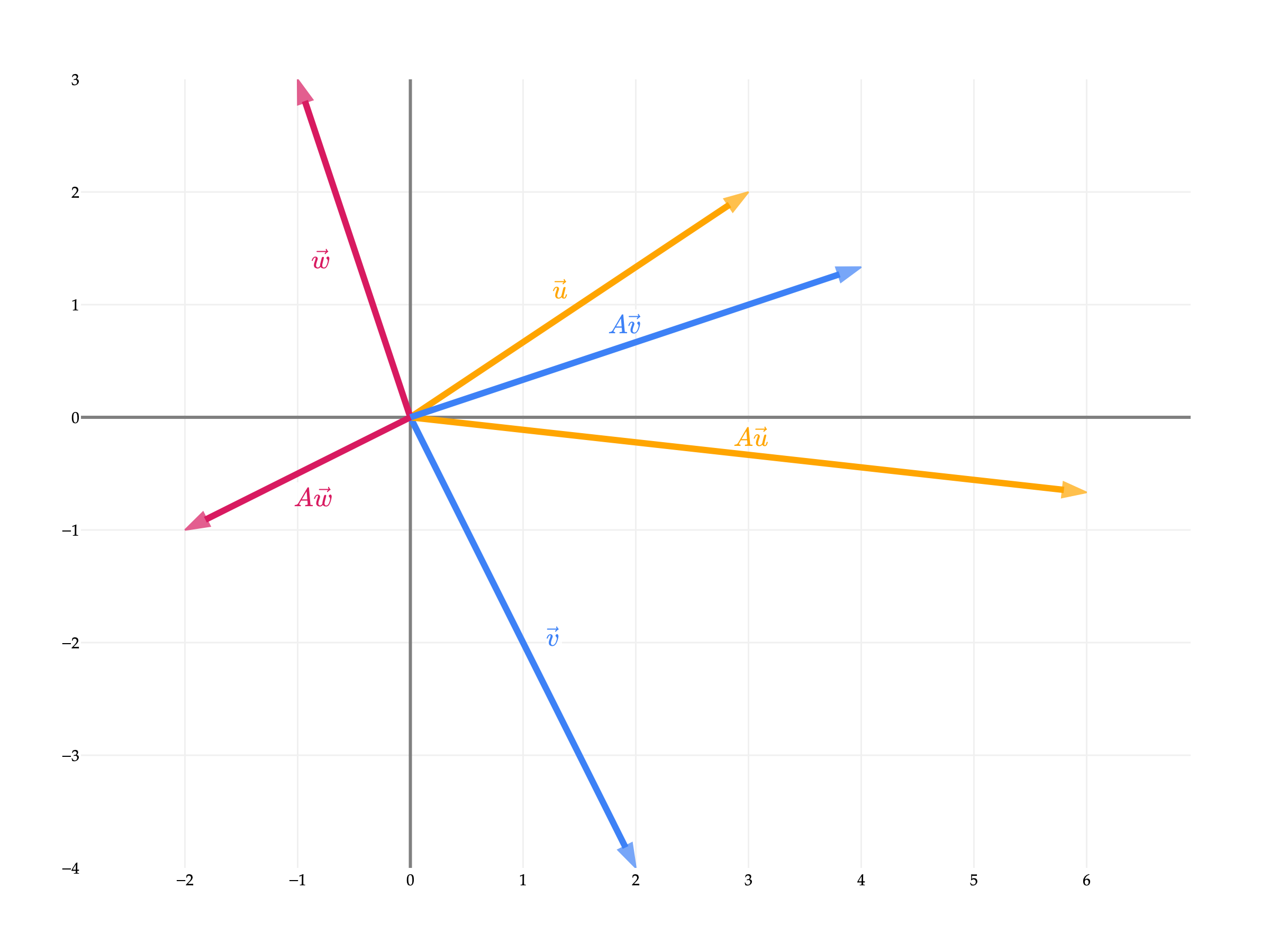

To start, let’s consider the linear transformation defined by the matrix

What happens to a vector in when we multiply it by ? Let’s visualize the effect of on several vectors in .

scales, or stretches, the input space by a factor of 2 in the -direction and a factor of in the -direction.

Scaling¶

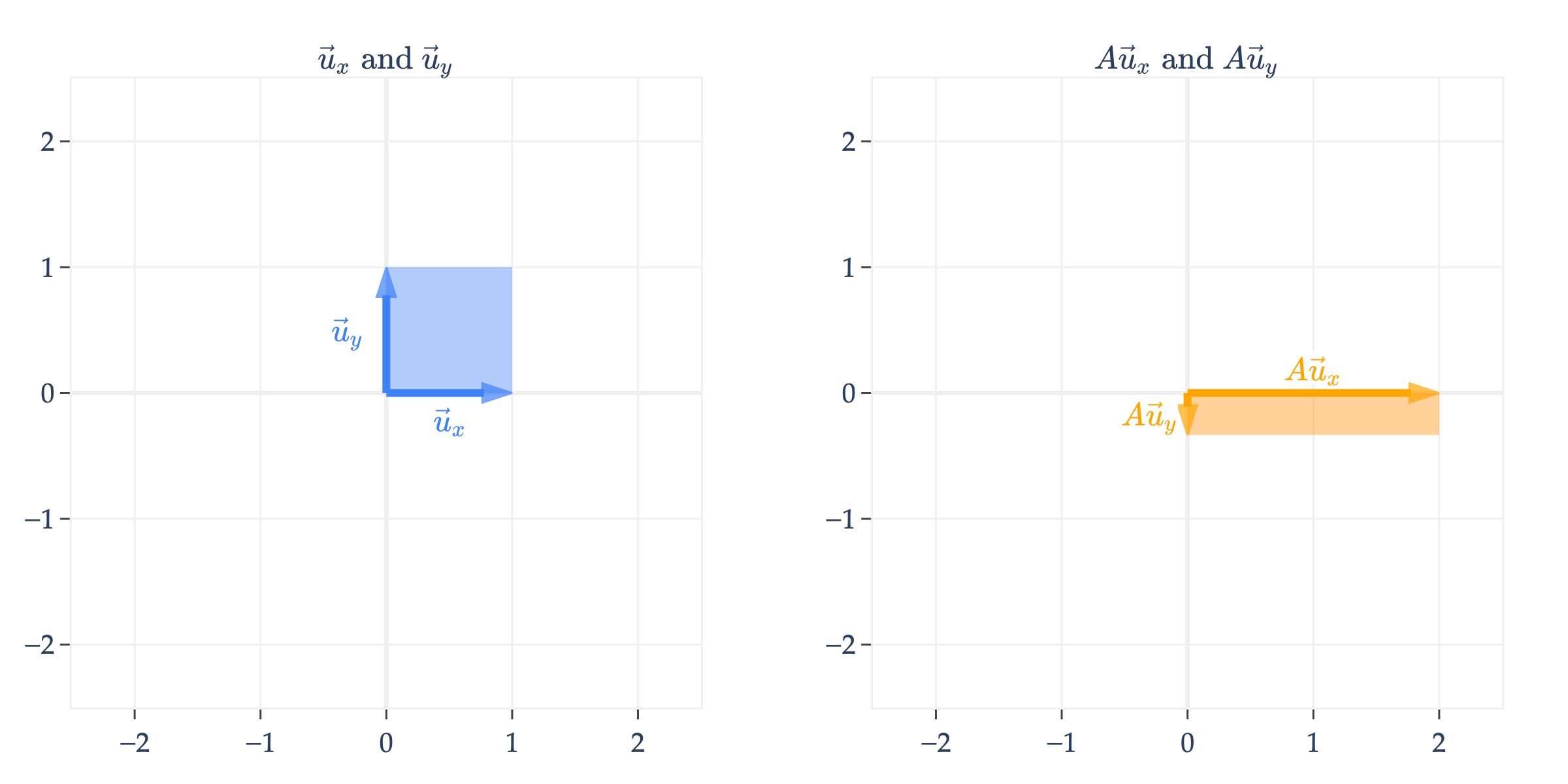

Another way of visualizing is to think about how it transforms the two standard basis vectors of , which are

(In the past I’ve called these and , but I’ll use and here since I’ll also use to represent a matrix shortly.)

Note that is just the first column of , and similarly is the second column of .

In addition to drawing and on the left and their transformed counterparts and on the right, I’ve also shaded in how the unit square, which is the square containing and , gets transformed. Here, it gets stretched from a square to a rectangle.

Remember that any vector is a linear combination of and . For instance,

So, multiplying by is equivalent to multiplying by a linear combination of and .

and the result is a linear combination of and with the same coefficients! If this sounds confusing, just remember that and are just the first and second columns of , respectively.

So, as we move through the following examples, think of the transformed basis vectors and as a new set of “building blocks” that define the transformed space (which is the column space of ).

is a diagonal matrix, which means it scales vectors. Note that any vector in can be transformed by , not just vectors on or within the unit square; I’m just using these two basis vectors to visualize the transformation.

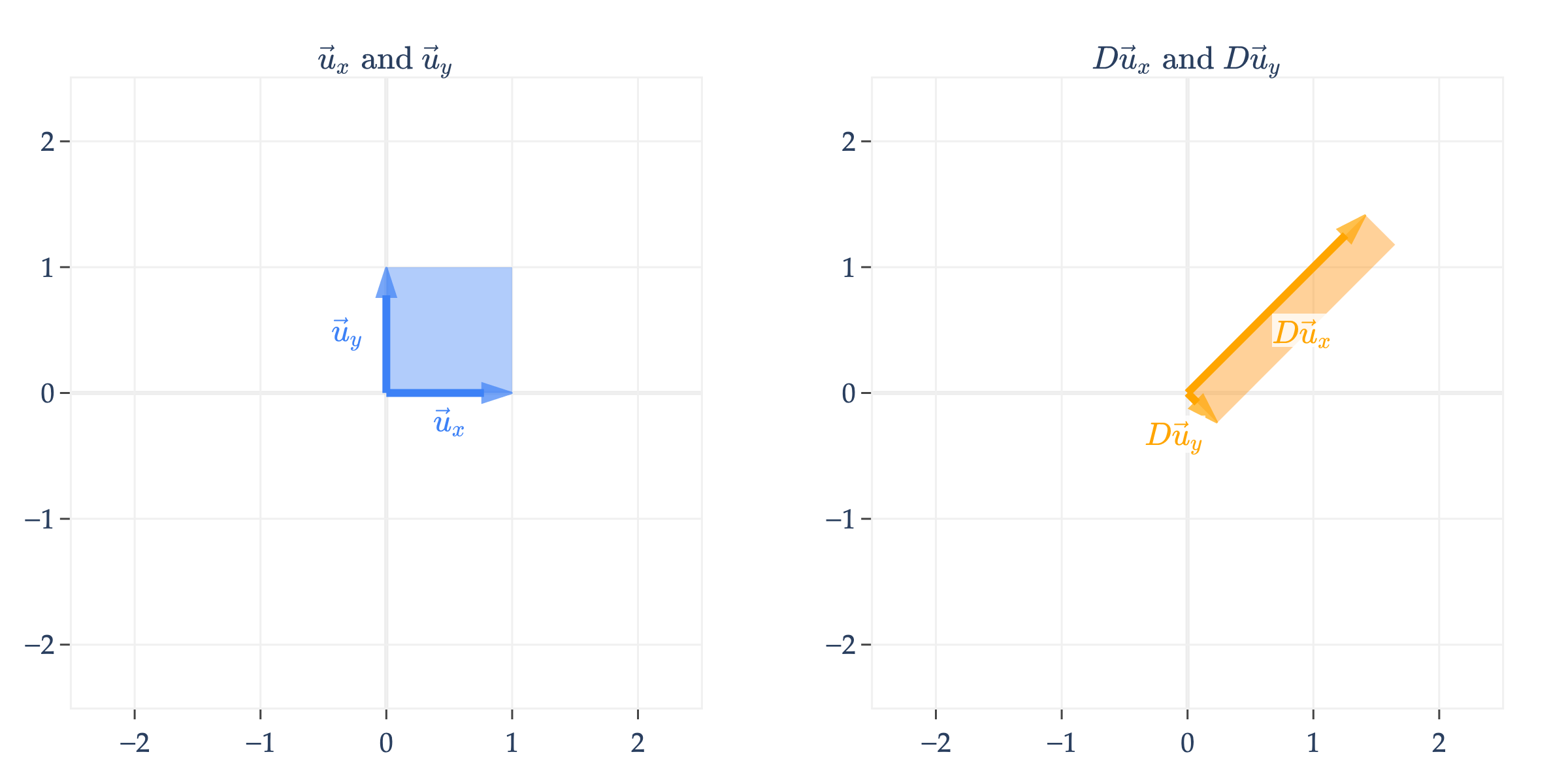

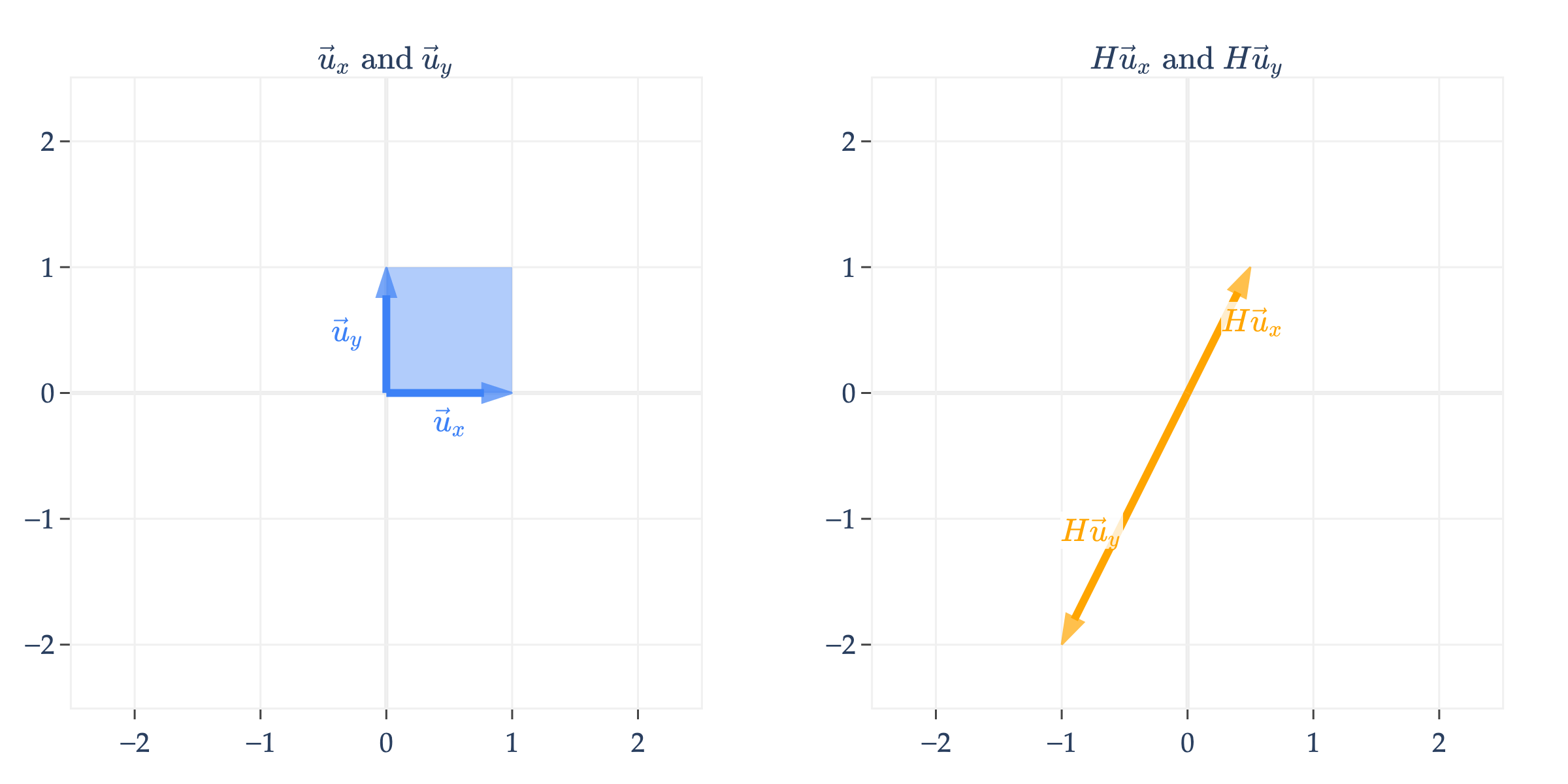

Rotations and Orthogonal Matrices¶

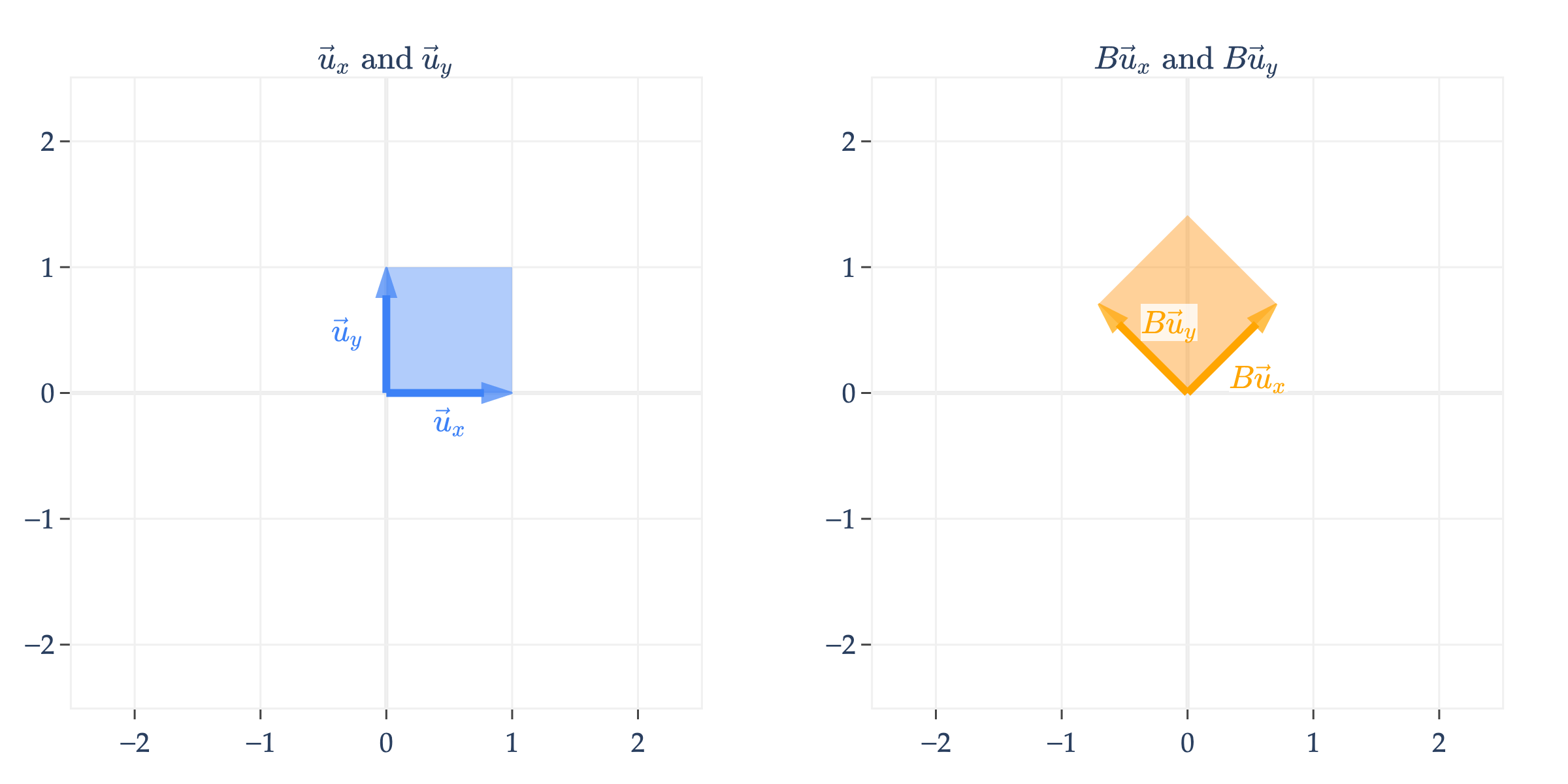

What might a non-diagonal matrix do? Let’s consider

Just to continue the previous example, the vector is transformed into

is an orthogonal matrix, which means that its columns are unit vectors and are orthogonal to one another.

Orthogonal matrices rotate vectors in the input space. In general, a matrix that rotates vectors by (radians) counterclockwise in is given by

rotates vectors by radians, i.e. .

Rotations are more difficult to visualize in and higher dimensions, but in Homework 5, you’ll prove that orthogonal matrices preserve norms, i.e. if is an orthogonal matrix and , then . So, even though an orthogonal matrix might be doing something harder to describe in , we know that it isn’t changing the lengths of the vectors it’s multiplying.

To drive home the point I made earlier, any vector , once multiplied by , ends up transforming into

Composing Transformations¶

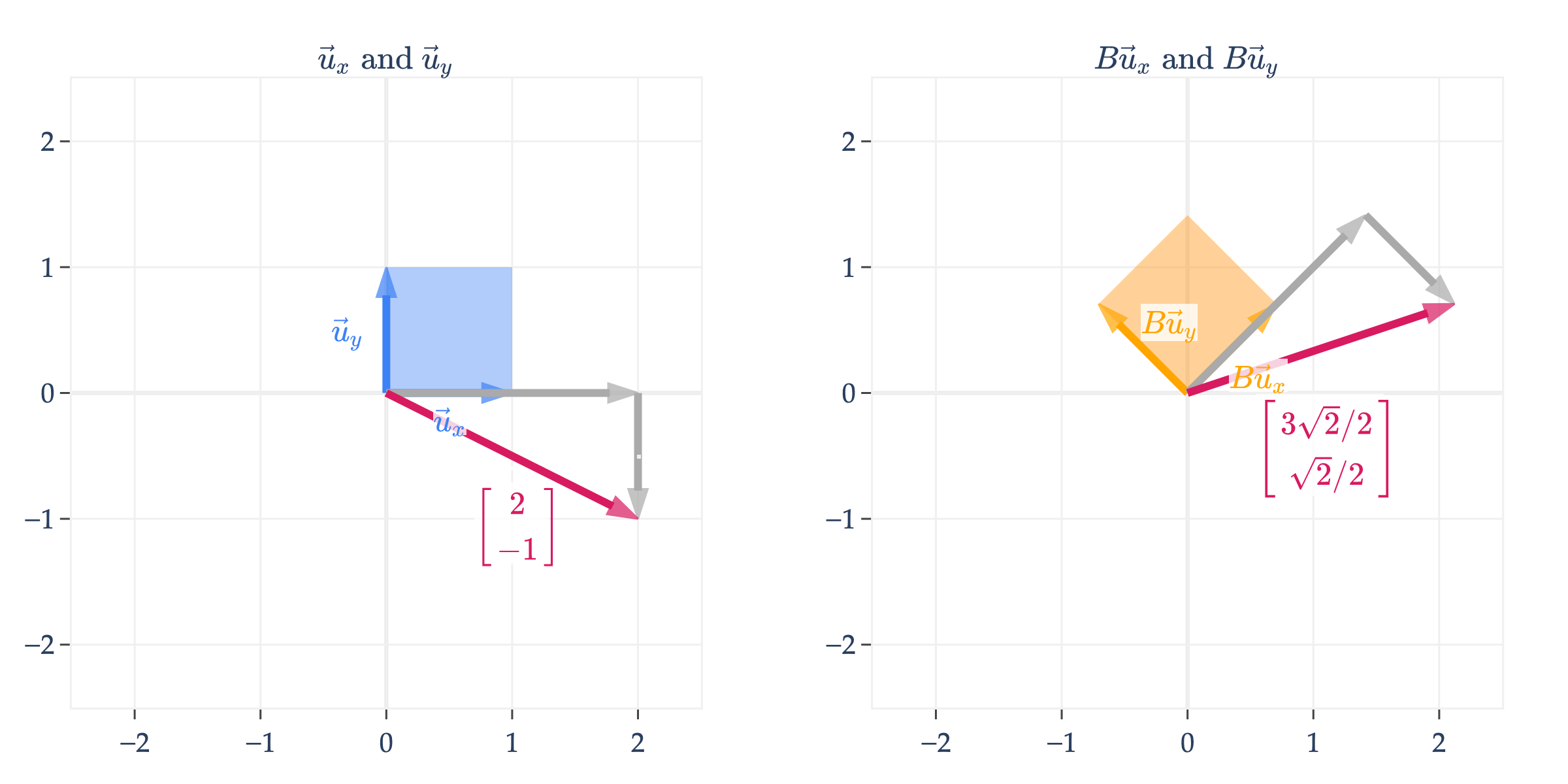

We can even apply multiple transformations one after another. This is called composing transformations. For instance,

is just

Note that rotates the input vector, and then scales it. Read the operations from right to left, since .

is different from

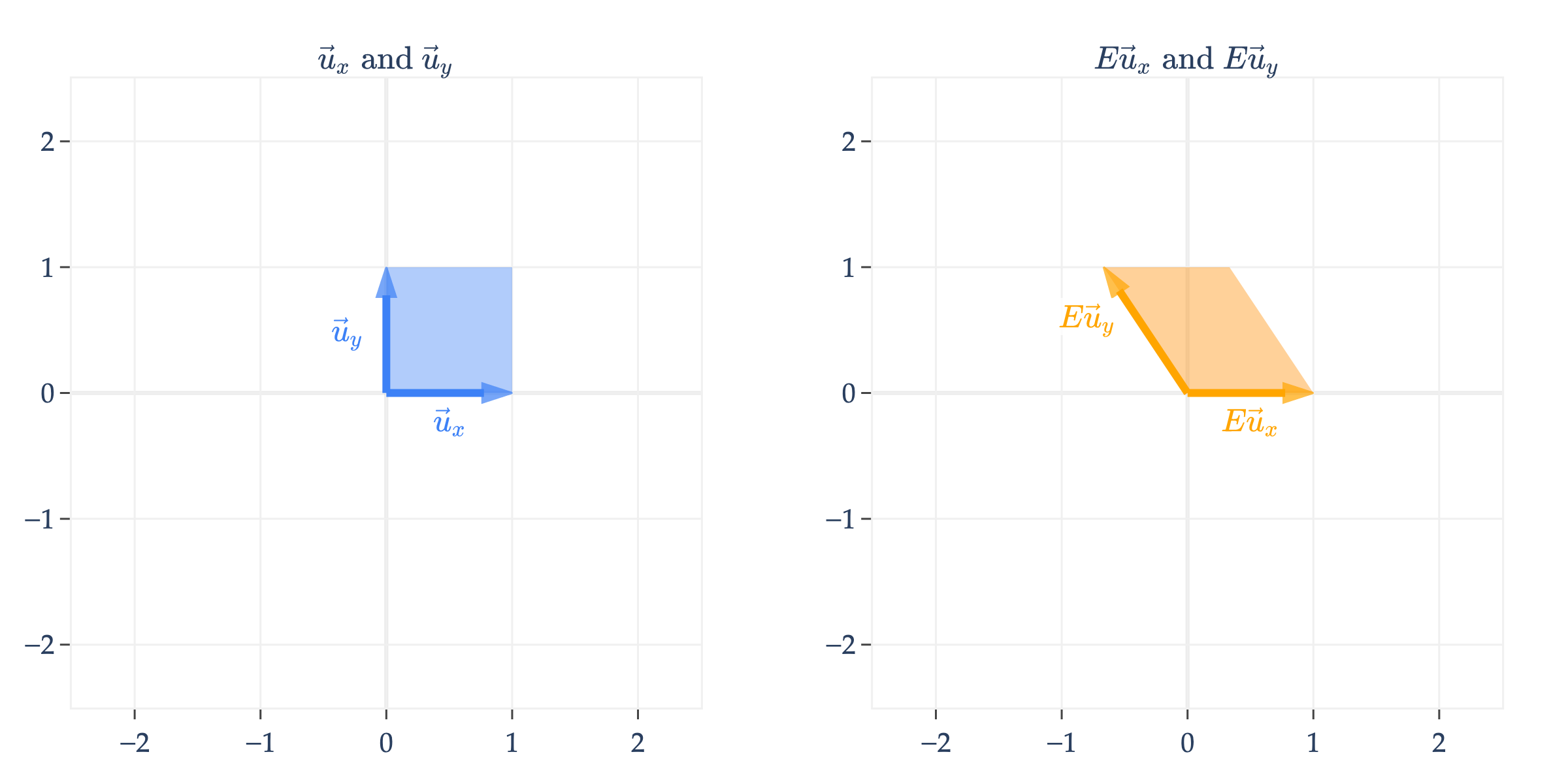

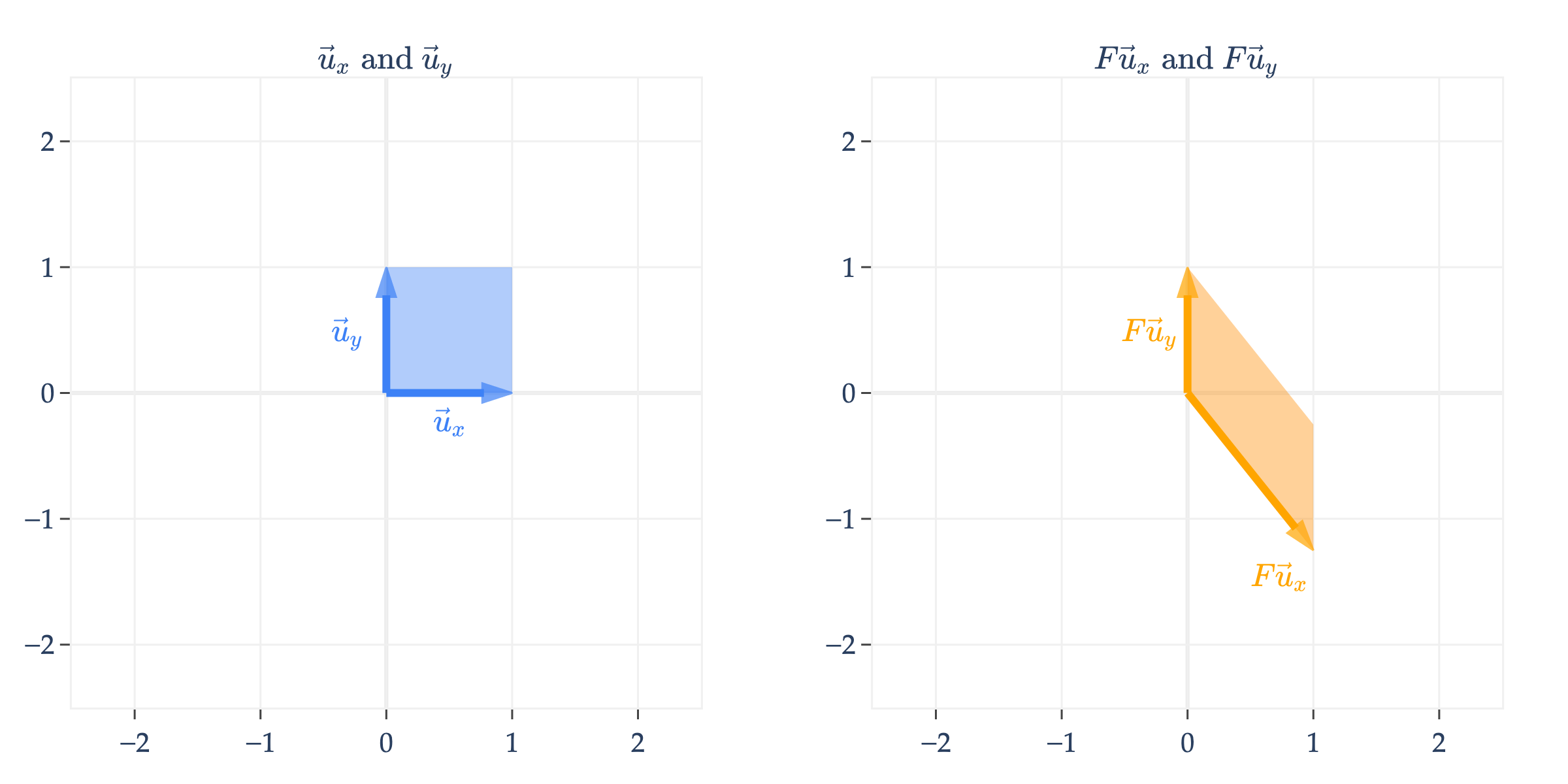

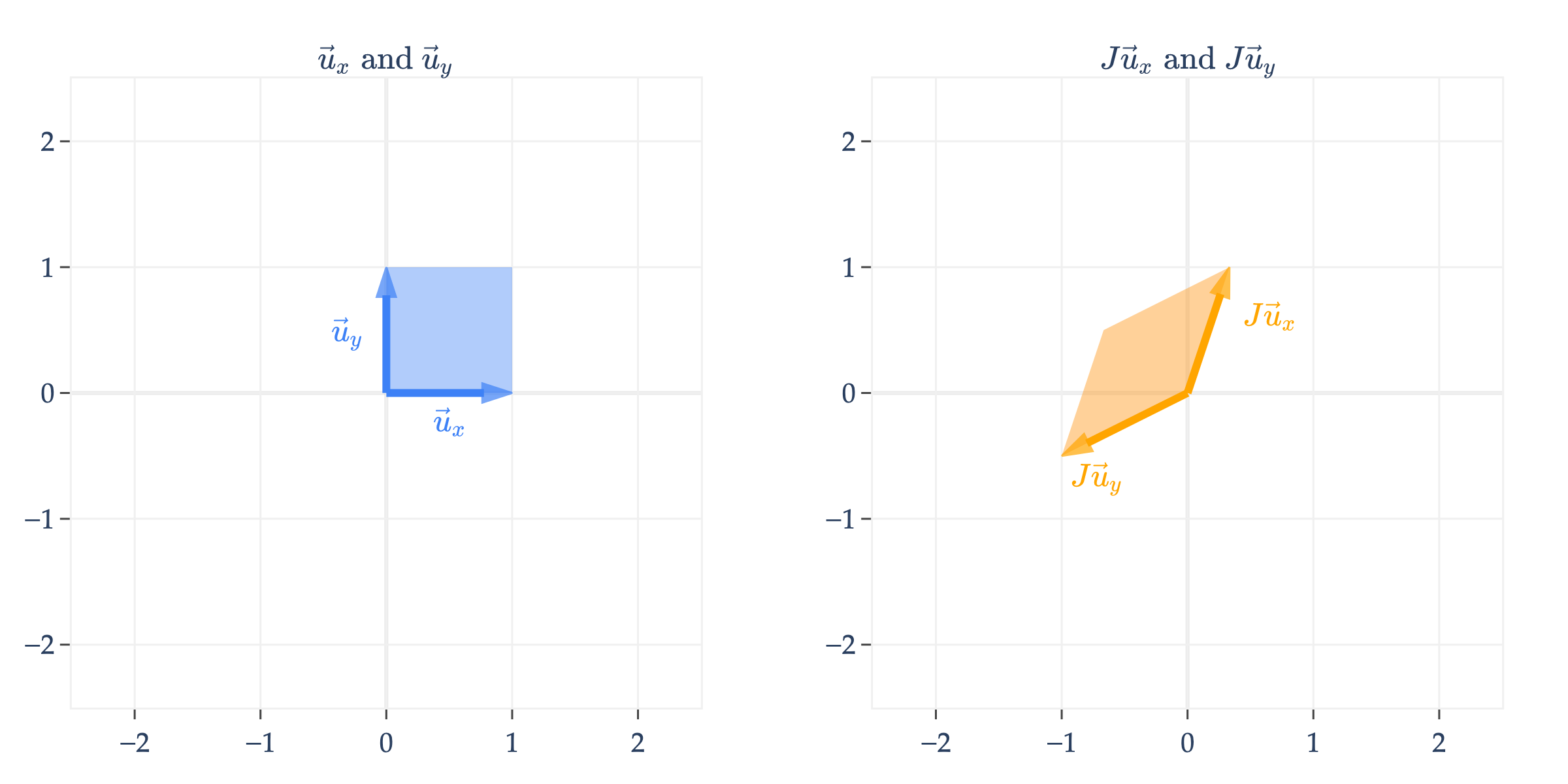

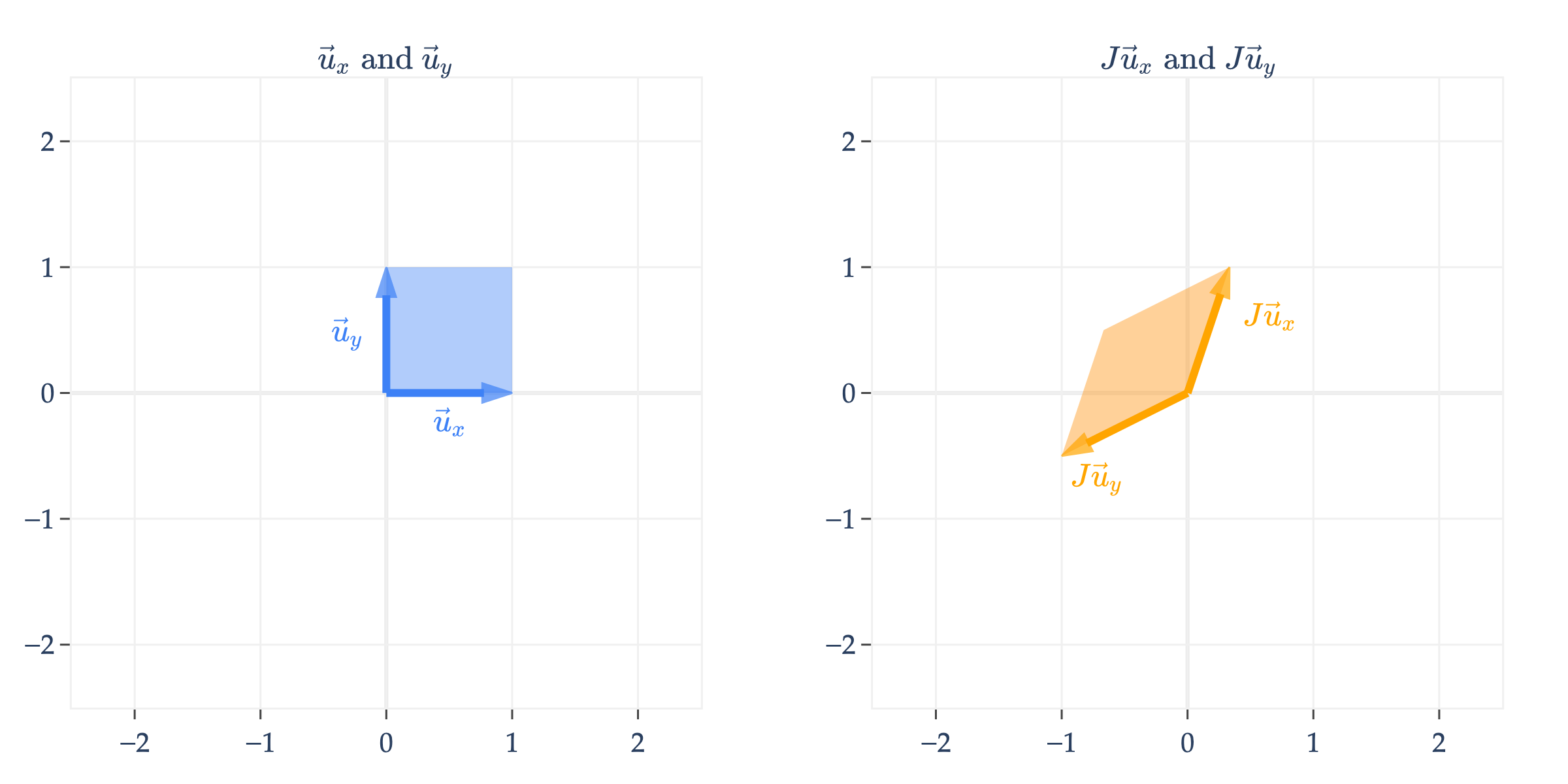

Shears¶

is a shear matrix. Think of a shear as a transformation that slants the input space along one axis, while keeping the other axis fixed. What helps me interpret shears is looking at them formulaically.

Note that the -coordinate of input vectors in remain unchanged, while the -coordinate is shifted by , which results in a slanted shape.

Similarly, is a shear matrix that keeps the -coordinate fixed, but shifts the -coordinate, resulting in a slanted shape that is tilted downwards.

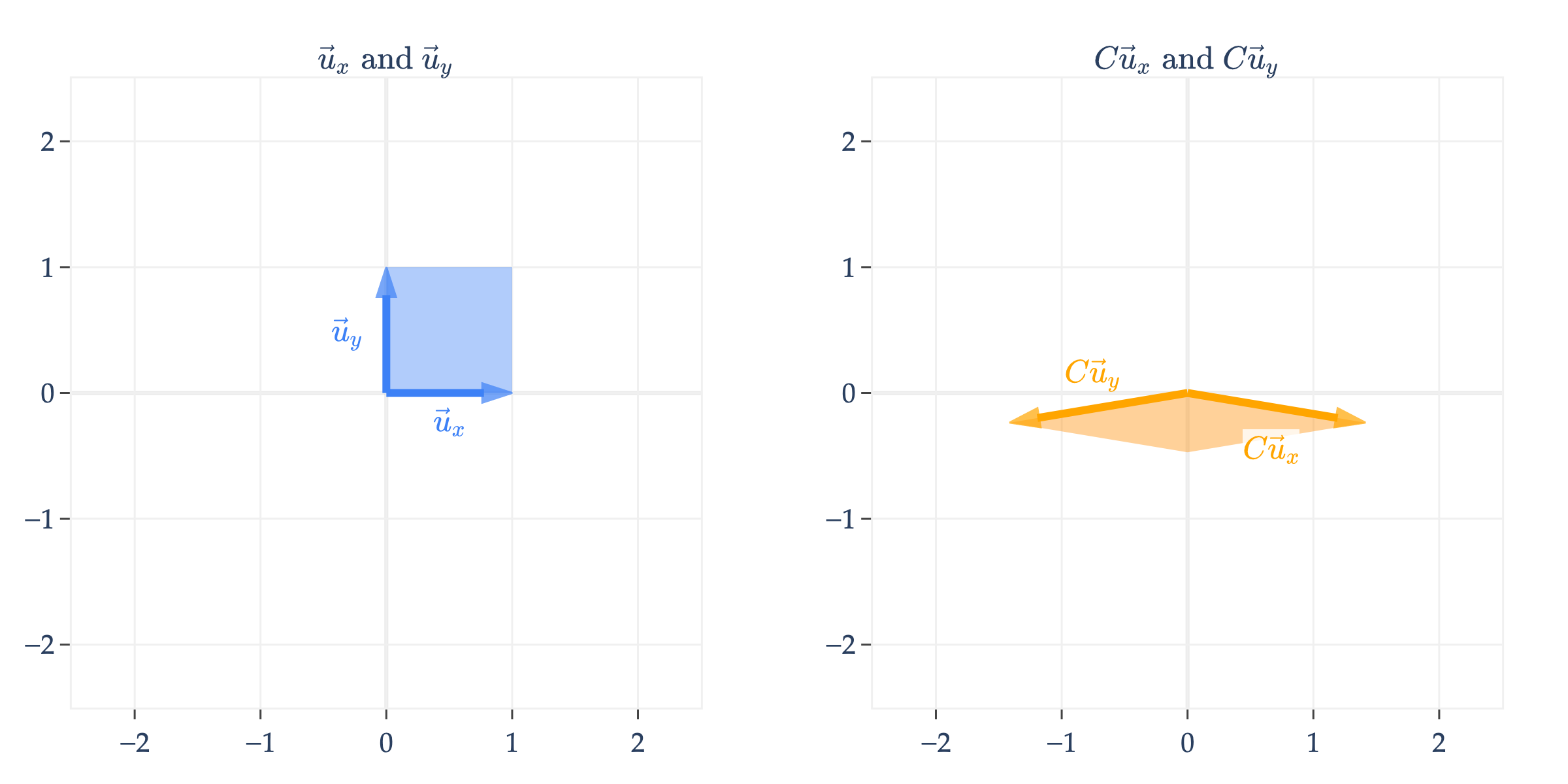

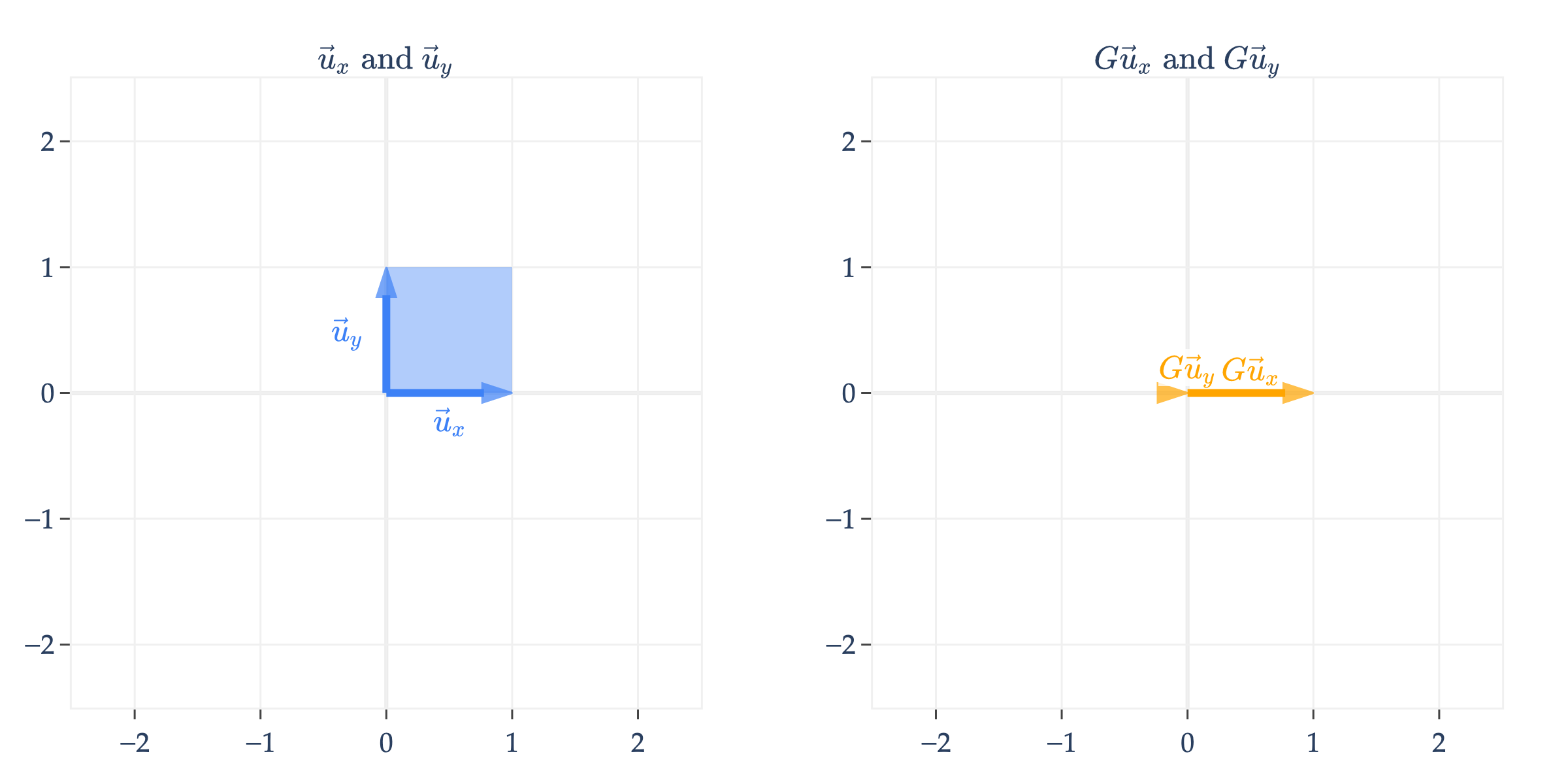

Projections¶

So far we’ve looked at scaling, rotation, and shear matrices. Yet another type is a projection matrix.

projects onto the -axis and throws away the -coordinate. Note that maps the unit square to a line, not another four-sided shape.

You might also notice that, unlike the matrices we’ve seen so far, is not all of , but rather it’s just a line in , since ’s columns are not linearly independent.

below works similarly.

is the line spanned by , so will always be some vector on this line.

Put another way, if , then is

but since and are both on the line spanned by , is really just a scalar multiple of .

Arbitrary Matrices¶

Finally, I’ll comment that not all linear transformations have a nice, intuitive interpretation. For instance, consider

turns the unit square into a parallelogram. In fact, so did , , , , , and ; all of these transformations map the unit square to a parallelogram, with some additional properties (e.g. ’s parallelogram was a rectangle, ’s had equal sides, etc.).

There’s no need to memorize the names of these transformations – after all, they only apply in and perhaps where we can visualize.

Speaking of , an arbitrary matrix can be thought of as a transformation that maps the unit cube to a parallelepiped (the generalization of a parallelogram to three dimensions).

What do you notice about the transformation defined by , and how it relates to ’s columns? (Drag the plot around to see the main point.)

Since ’s columns are linearly dependent, maps the unit cube to a flat parallelogram.

The Determinant¶

It turns out that there’s a formula for

area of the parallelogram formed by transforming the unit square by a matrix

volume of the parallelepiped formed by transforming the unit cube by a matrix

in general, the -dimensional “volume” of the object formed by transforming the unit -cube by an matrix

That formula is called the determinant of , and is denoted .

Why do we care? Remember, the goal of this section is to find the inverse of a square matrix , if it exists, and the determinant will give us one way to check if it does.

In the case of the projection matrices and above, we saw that their columns were linearly dependent, and so the transformations and mapped the unit square to a line with no area. Similarly above, mapped the unit cube to a flat parallelogram with no volume. In all other transformations, the matrices’ columns were linearly independent, so the resulting object had a non-zero area (in the case of matrices) or volume (in the case of matrices).

So, how do we find ? Unfortunately, the formula is only convenient for matrices.

For example, in the transformation

the area of the parallelogram formed by transforming the unit square is

Note that a determinant can be negative! So, to be precise, describes the -dimensional volume of the object formed by transforming the unit -cube by .

The sign of the determinant depends on the order of the columns of the matrix. For example, swap the columns of and its determinant would be . (If is “to the right” of , the determinant is positive, like with the standard basis vectors; if is “to the left” of , the determinant is negative.)

The determinant of an matrix can be expressed recursively using a weighted sum of determinants of smaller matrices, called minors. For example, if is the matrix

then is

The matrix is a minor of ; it’s formed by deleting the first row and first column of . Note the alternating signs in the formula. This formula generalizes to matrices, but is not practical for anything larger than . (What is the runtime of this algorithm?)

The computation of the determinant is not super important. The big idea is that the determinant of is a single number that tells us whether ’s transformation “loses a dimension” or not.

Some useful properties of the determinant are that, for any matrices and ,

(notice the exponent!)

If results from swapping two of ’s columns (or rows), then

The proofs of these properties are beyond the scope of our course. But, it’s worthwhile to think about what they mean in English in the context of linear transformations.

implies that the rows of (which are the columns of ) create the same “volume” as the columns of .

matches our intuition that linear transformations can be composed. is the result of applying to , then to the result.

multiplies each column of by , and so the volume of the resulting object is scaled by .

If results from swapping two of ’s columns (or rows), then reflects that swapping two columns reverses the orientation of the transformation, flipping the signed volume from positive to negative (or vice versa) while preserving its magnitude.

This YouTube playlist contains walkthrough videos of the following activity, which has 5 subparts. The first video, embedded below, contains a brief overview of determinants, summarizing the content above.

Activity 2¶

Activity 2

Activity 2.1

Find the determinant of the following matrices:

Walkthrough video

Activity 2.2

Suppose and are both matrices. Is in general?

Walkthrough video

Activity 2.3

Suppose we multiply ’s 2nd column by 3. What happens to ?

Walkthrough video

Activity 2.4

If ’s columns are linearly dependent, then find .

Walkthrough video

Activity 2.5

Find the determinant of (Hint: The answer does not depend on !).

is a orthogonal matrix. If is an orthogonal matrix, then what is ?

Walkthrough video

Now that we have a better understanding of the linear transformations that are implicitly defined by square matrices, we can return to the question of inverses, when they exist, and how to find them.