Introduction¶

In Chapter 10.3, we found the best direction for representing data by minimizing orthogonal projection error (equivalently, maximizing projected variance). We now use that result to define principal components and connect them to the SVD.

Principal Components¶

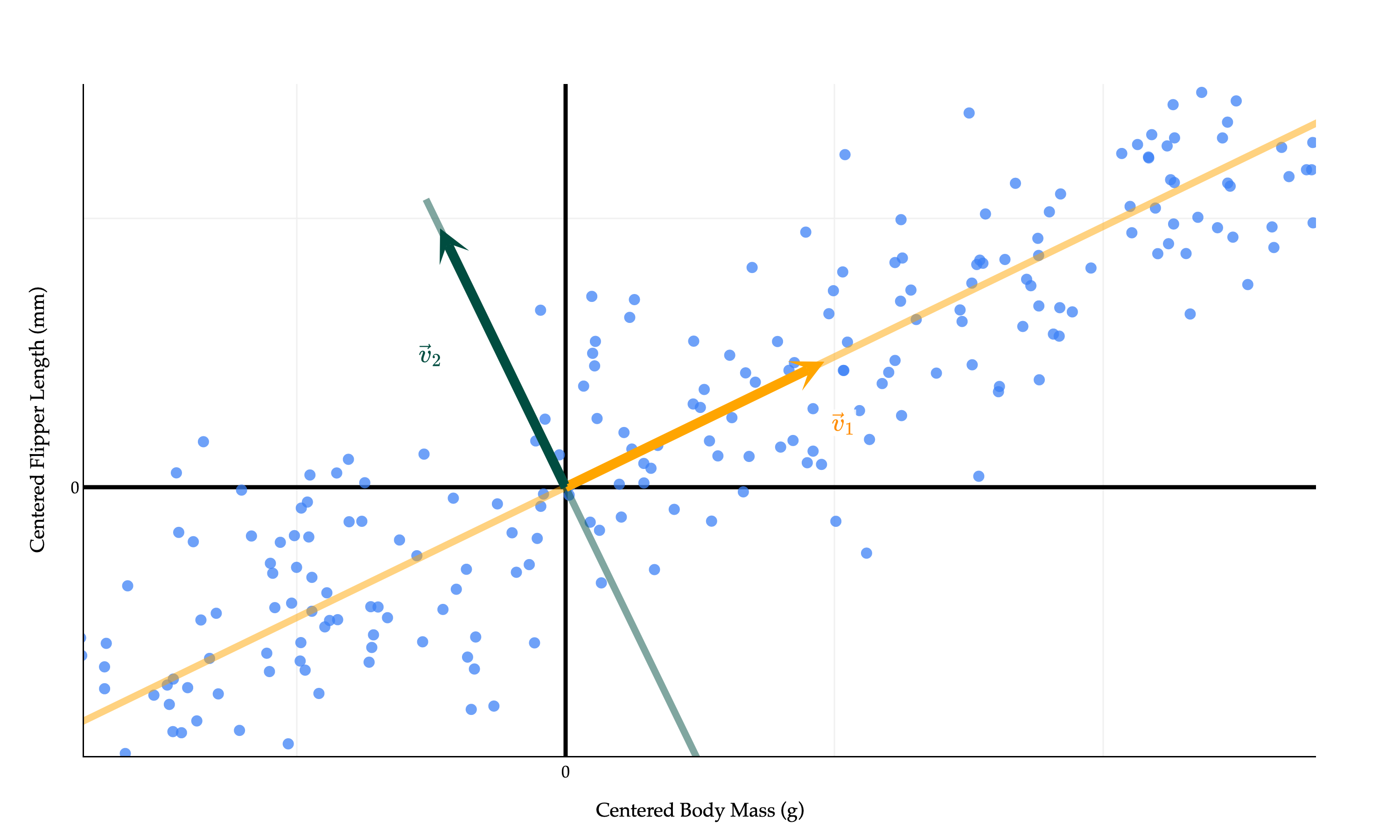

We’ve discovered that the single best direction to project the data onto is the eigenvector of corresponding to the largest eigenvalue of . Let’s call this eigenvector , as I did in the diagram above. More ’s are coming.

The values of the first principal component, (i.e. new feature 1), come from projecting each row of onto :

This projection of our data onto the line spanned by is the linear combination of the original features that captures the largest possible amount of variance in the data.

(Whenever you see “principal component”, you should think “new feature”.)

Remember, one of our initial goals was to find multiple principal components that were uncorrelated with each other, meaning their correlation coefficient is 0. We’ve found the first principal component, , which came from projecting onto the best direction. This is the single best linear combination of the original features we can come up with.

Let’s take a greedy approach. I now want to find the next best principal component, , which should be uncorrelated with . should capture all of the remaining variance in the data that couldn’t capture. Intuitively, since our dataset is 2-dimensional, together, and should contain the same information as the original two features.

comes from projecting onto the best direction among all directions that are orthogonal to . It can be shown that this “second-best direction” is the eigenvector of corresponding to the second largest eigenvalue of .

In other words, the vector that maximizes subject to the constraint that is orthogonal to , is . The proof of this is beyond the scope of what we’ll discuss here, as it involves some constrained optimization theory.

Why is orthogonal to ? They are both eigenvectors of corresponding to different eigenvalues, so they must be orthogonal, thanks to the spectral theorem (which applies because is symmetric). Remember that while any vector on the line spanned by is also an eigenvector of corresponding to the second largest eigenvalue, we pick the specific that is a unit vector.

and being orthogonal means that and are orthogonal, too. But because the columns of are mean centered, we can show that this implies that the correlation between and is 0. I’ll save the algebra for now, but see if you can work this out yourself. You’ve done similar proofs in homeworks already.

The SVD Returns¶

The moment I said that is an eigenvector of , something should have been ringing in your head: is a singular vector of ! Recall, if

is the singular value decomposition of , then the columns of are the eigenvectors of , all of which are orthogonal to each other and have unit length.

We arranged the components in the singular value decomposition in decreasing order of singular values of , which are the square roots of the eigenvalues of .

So,

the first column of is , the “best direction” to project the data onto,

the second column of is , the “second-best direction” to project the data onto,

the third column of is , the “third-best direction” to project the data onto,

and so on.

Let’s put this in context with a few examples.

Example: From to ¶

Let’s start with the 2-dimensional dataset of flipper length vs. body mass from the penguins dataset.

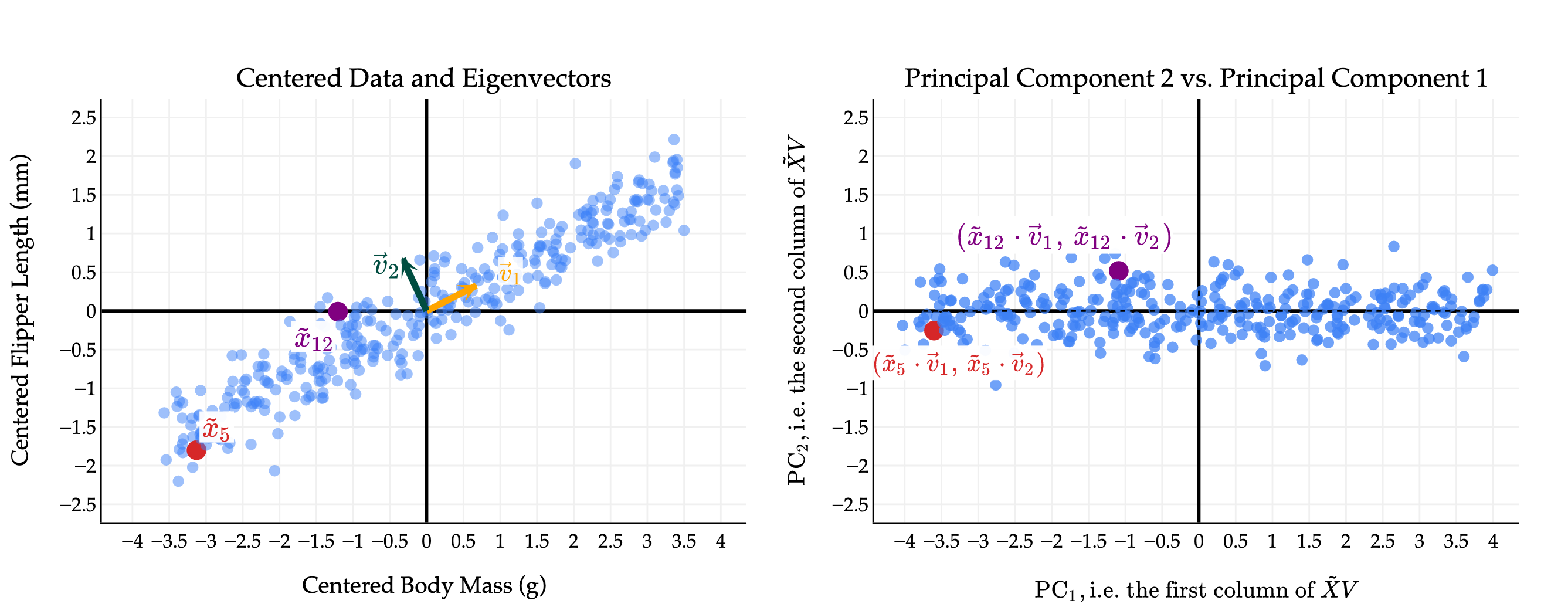

The first thing you should notice is that while the original data points seem to have some positive correlation, the principal components are uncorrelated! This is a good thing; it’s what we wanted as a design goal. In effect, by converting from the original features to principal components, we’ve rotated the data to remove the correlation between the features.

I have picked two points to highlight, points 5 and 12 in the original data. The coloring in red and purple is meant to show you how original (centered) data points translate to points in the principal component space.

Notice the scale of the data: axis is much longer than the axis, since the first principal component captures much more variance than the second. We will make this notion - of the proportion of variance captured by each principal component - more precise soon.

(You’ll notice that the body mass and flipper length values on the left are much smaller than in the original datasets; in the original dataset, the body mass values were in the thousands, which distorted the scale of the plot and made it hard to see that the two eigenvectors are indeed orthogonal.)

Example: Starting from ¶

The real power of PCA reveals itself when we start with high-dimensional data. Suppose we start with three of the features in the penguins dataset: bill_depth_mm, flipper_length_mm, and body_mass_g - and want to reduce the dimensionality of the data to 1 or 2. Points are colored by their species.

Observe that penguins of the same species tend to be clustered together. This, alone, has nothing to do with PCA: we happen to have this information, so I’ve included it in the plot.

If is the matrix of three features, and is the mean-centered version, the best directions in which to project the data are the columns of in .

X_three_featuresX_three_features.mean()bill_depth_mm 17.164865

flipper_length_mm 200.966967

body_mass_g 4207.057057

dtype: float64# This is the mean-centered version of X_three_features!

X_three_features - X_three_features.mean()X_three_features_centered = X_three_features - X_three_features.mean()

u, s, vt = np.linalg.svd(X_three_features_centered)Now, the rows of (vt), which are the columns of (vt.T), contain the best directions.

vtarray([[-1.15433983e-03, 1.51946036e-02, 9.99883889e-01],

[ 1.02947493e-01, -9.94570148e-01, 1.52327042e-02],

[ 9.94686122e-01, 1.02953123e-01, -4.16174416e-04]])It’s important to remember that these “best directions” are nothing more than linear combinations of the original features. Since the first row of is , the first principal component is

while the second is

and third is

where is the index of the penguin.

To compute all three of these principal components at once, for every penguin, we just need to compute .

pcs = X_three_features_centered @ vt.T

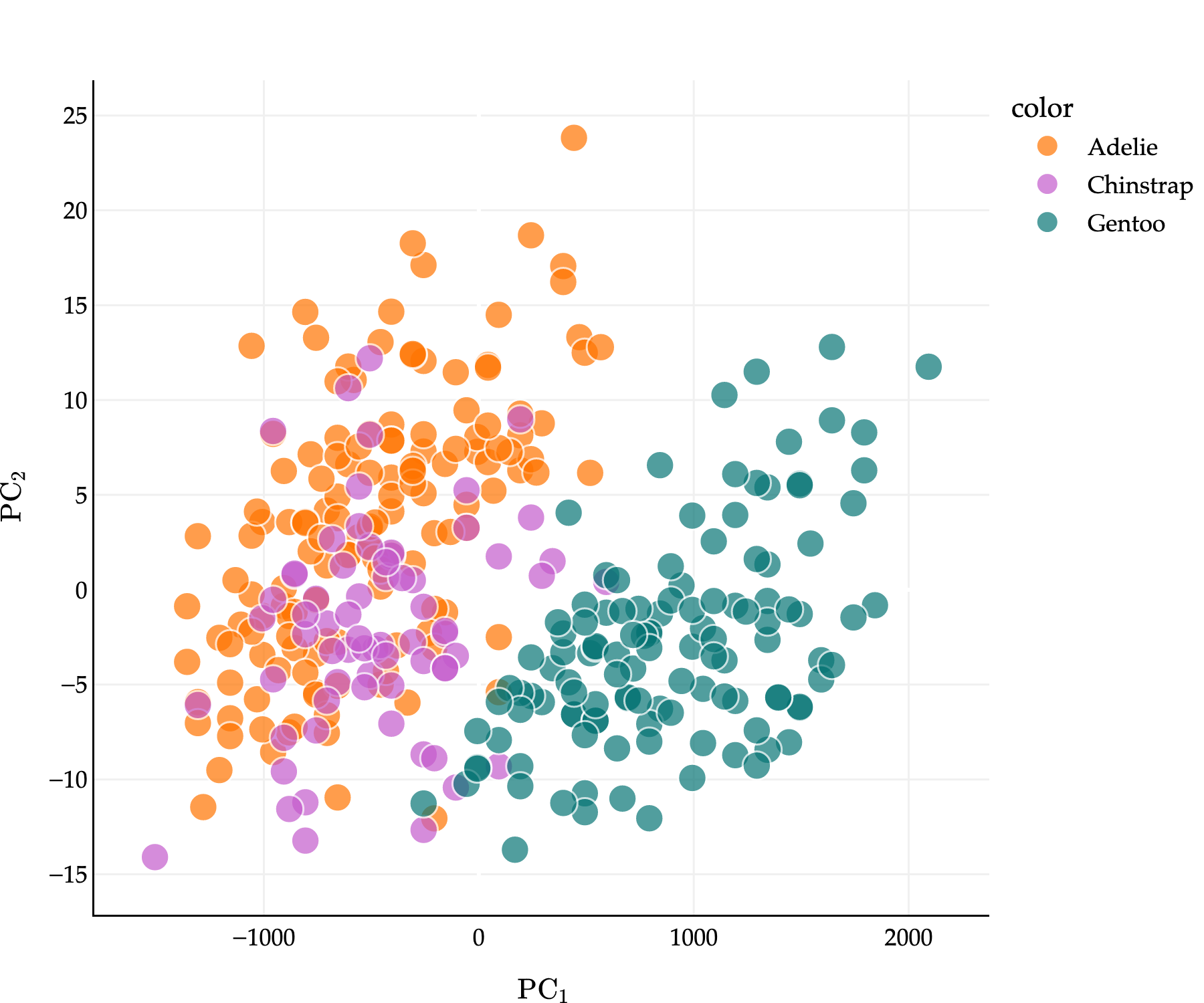

pcsLet’s plot the first two principal components: that is, for each of our 333 penguins, we’ll plot their value of on the -axis and their value of on the -axis.

This is the best 2-dimensional projection of our 3-dimensional scatter plot. And here’s the kicker: penguins of the same species STILL tend to be clustered together in the principal component space!

What this tells us is that our technique for taking linear combinations of the original features is good at preserving the important information in the original dataset. We went from writing down 3 numbers per penguin to 2, but it seems that we didn’t lose much information per penguin.

What do I mean by “much important information”? Let’s make this idea more precise.

Explained Variance¶

The goal of PCA is to find new features - principal components - that capture as much of the variation in the data as possible, while being uncorrelated with each other.

PCA isn’t foolproof: it works better on some datasets than others. If the features we’re working with are already uncorrelated, PCA isn’t useful. And, even for datasets that are well suited for PCA, we need a systematic way to decide how many principal components to use. So far, we’ve often used 1 or 2 principal components for the purposes of visualization, but in general, we need a more systematic approach. What if we start with an matrix and want to decide how many principal components to compute?

Let’s define the total variance of an matrix as the sum of the variances of the columns of . If is the -th value of the -th feature, and is the mean of the -th feature, then the total variance of is

Let’s compute this for X_three_features.

X_three_features.var(ddof=0) # The variances of the individual columns of X.bill_depth_mm 3.866243

flipper_length_mm 195.851762

body_mass_g 646425.423171

dtype: float64X_three_features.var(ddof=0).sum()646625.1411755901So, the total variance of X_three_features is approximately 646625.

This is also equal to the sum of the variances of the columns of , i.e. the sum of the variances of the principal components!

# These three numbers are DIFFERENT than the numbers above,

# but their sum is the same.

(X_three_features_centered @ vt.T).var(ddof=0)0 646575.552578

1 47.055776

2 2.532822

dtype: float64(X_three_features_centered @ vt.T).var(ddof=0).sum() # Same sum as before.646625.1411755901Why? If we create the same number of principal components as we have original features, we haven’t lost any information - we’ve just written the same data in a different basis. The goal, though, is to pick a number of principal components that is relatively small (smaller than the number of original features), but still captures most of the variance in the data.

Each new principal component - that is, each column of - captures some amount of this total variance. What we’d like to measure is the proportion (that is, fraction, or percentage) of the total variance that each principal component captures. The first principal component captures the most variance, since it corresponds to the direction in which the data varies the most. The second principal component captures the second-most variance, and so on. But how much variance does the first, second, or -th principal component capture?

Recall from earlier that the variance of the data projected onto a vector is given by

maximizes this quantity, which is why the first principal component is the projection of the data onto ; maximizes the quantity subject to being orthogonal to , and so on.

Then, the variance of is whatever we get back when we plug into the formula above, and in general, the variance of is (again, where is the -th column of in the SVD of ). Observe that if is the -th column of in , then,

Here, we used the ever important fact that , where is the -th singular value of and is the -th column of in the SVD of .

What this tells us is that the variance of the -th principal component is . This is a beautiful result - it tells us that the variance of the -th principal component is simply the square of the -th singular value of , divided by . The ’s in the SVD represent the amount that the data varies in the direction of ! We don’t need any other fancy information to compute the variance of the principal components; we don’t need to know the individual principal component values, or have access to a variance method in code.

u, s, vt = np.linalg.svd(X_three_features_centered)

sarray([14673.43378383, 125.1781673 , 29.04185933])np.set_printoptions(precision=8)n = X_three_features_centered.shape[0]

variances_of_pcs = s ** 2 / n

np.set_printoptions(suppress=True)

variances_of_pcsarray([646575.55257751, 47.05577648, 2.5328216 ])Above, we see the exact same values as if we computed the variances of the principal components directly from the data.

(X_three_features_centered @ vt.T).var(ddof=0)0 646575.552578

1 47.055776

2 2.532822

dtype: float64Since the total variance of is the sum of the variances of its principal components, the total variance of is then the sum of over all , where . (Remember that if , then .)

So, if we single out just one principal component, how much of the overall variation in does it capture? The answer is given by the proportion of variance explained by the -th principal component:

This is a number between 0 and 1, which we can interpret as a percentage.

s # The singular values of X_three_features.array([14673.43378383, 125.1781673 , 29.04185933])(s ** 2) / (s ** 2).sum() # The proportions of variance explained by each principal component.array([0.99992331, 0.00007277, 0.00000392])The above tells us that in X_three_features, the first principal component captures 99.99% of the variance in the data! There’s very little information lost in projecting this 3-dimensional dataset into 1-dimensional space.

Often, the proportions above are visualized in a scree plot, as you’ll see in Homework 11. Scree plots allow us to visually decide the number of principal components to keep, based on where it seems like we’ve captured most of the variation in the data. We’ll work on a related example in live lecture.

The PCA Recipe¶

Let’s briefly summarize what I’ll call the “PCA recipe”, which describes how to find the principal components (new features) of a dataset.

Starting with an matrix of data points in dimensions, mean-center the data by subtracting the mean of each column from itself. The new matrix is .

Compute the singular value decomposition of : . The columns of (rows of ) describe the directions of maximal variance in the data.

Principal component comes from multiplying by the -th column of .

The resulting principal components - which are the columns of - are uncorrelated with one another.

The variance of is . The proportion of variance explained by is